One of the most shiny uses of generative AI is when AI replicates the most human of things- our appearance. Its eye-catching, sure, but is also the space where we could see the most apparent, noisy and insidious of disruptions.

And much of it is well underway.

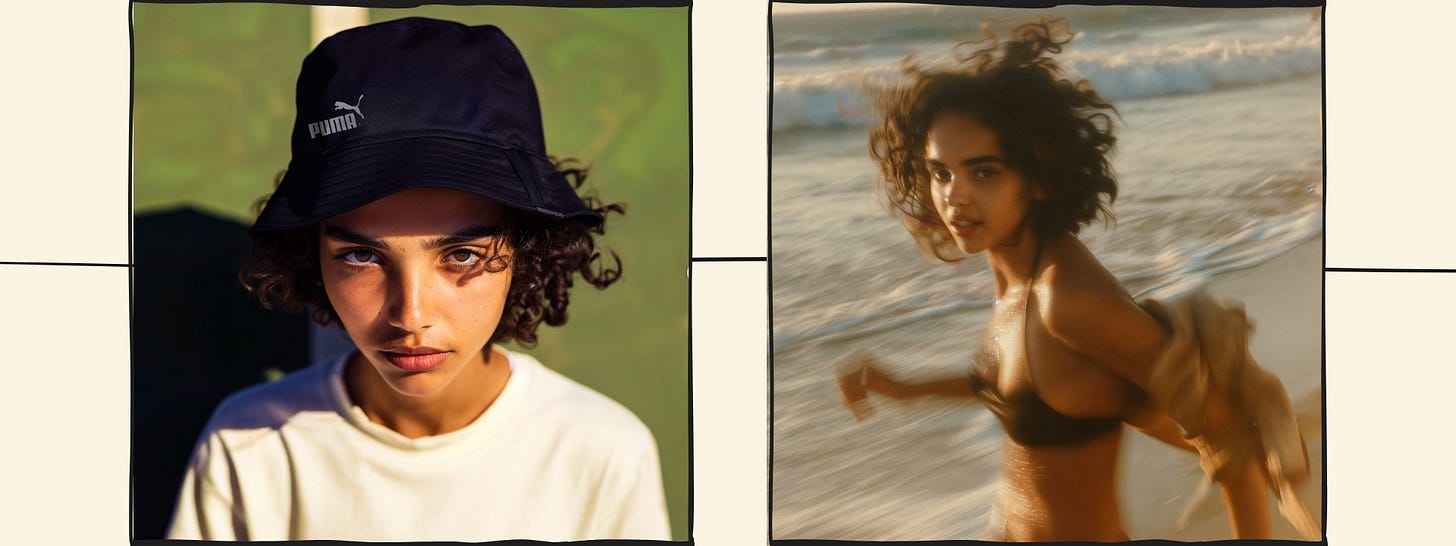

Two recent stories prompt this piece. Mango released its second campaign using AI models, though the threads these AI models wear are real, and available to buy. Elsewhere, Puma has partnered with- sorry, ‘launched’- a Moroccan AI influencer. Laila Khadraa is a 21-year-old Moroccan marketing student, sports fanatic, loves football, running, surfing, is a foodie, fashion buff, sneakerhead and lover of Casablanca. Phew!

A breeze through Laila’s posts immediately shows you the tremendous strides we have made in virtual or AI-generated digital entities. Her words, activities and nifty combos with locations and real clips, bring her precariously close to looking like a fresh creator looking to make her mark. Much of it is clever.

Yet, as with much in the generative world, that is not all. There are questions around authenticity, transparency and representation.

Questions worth a moment or two of our time.

Can audiences tell this is AI? Should they be told more clearly (besides a perfunctory bio note?). Is there thought given to how this affects teenage girls’ perceptions of beauty? Why does Laila look so young sometimes? Is the entire thing also a convenient bypass of cultural norms because you can ‘make’ the model do whatever you please? “Skip past any cultural barriers and go straight to the pouting selfies“, says Hena Husain. Yes, that question of representation & authenticity.

Kian Bakhtiari looks at it from the perspective of diversity. ”Using AI Influencers to improve diversity is like generating JPEG images of trees to tackle the global climate crisis”, and this kind of initiative “reveals how the advertising industry views diversity as a ‘casting exercise’ rather than an opportunity to better represent society.”

Though this case seems like a Moroccan creation for a Moroccan consumer base, not global, these are still valid points. Could they have worked with Moroccan creators? Could they have been part of an authentic story or three, with real Moroccan youth? They could.

Also, could they have found a cheaper alternative to real humans, for crafting faux-authenticity and retaining full control over the narrative, all while jumping on the trend of the year (all aboard for AI!)? They could have, and they did.

This is but a small hint of how creators- the great disruptors themselves- could be disrupted.

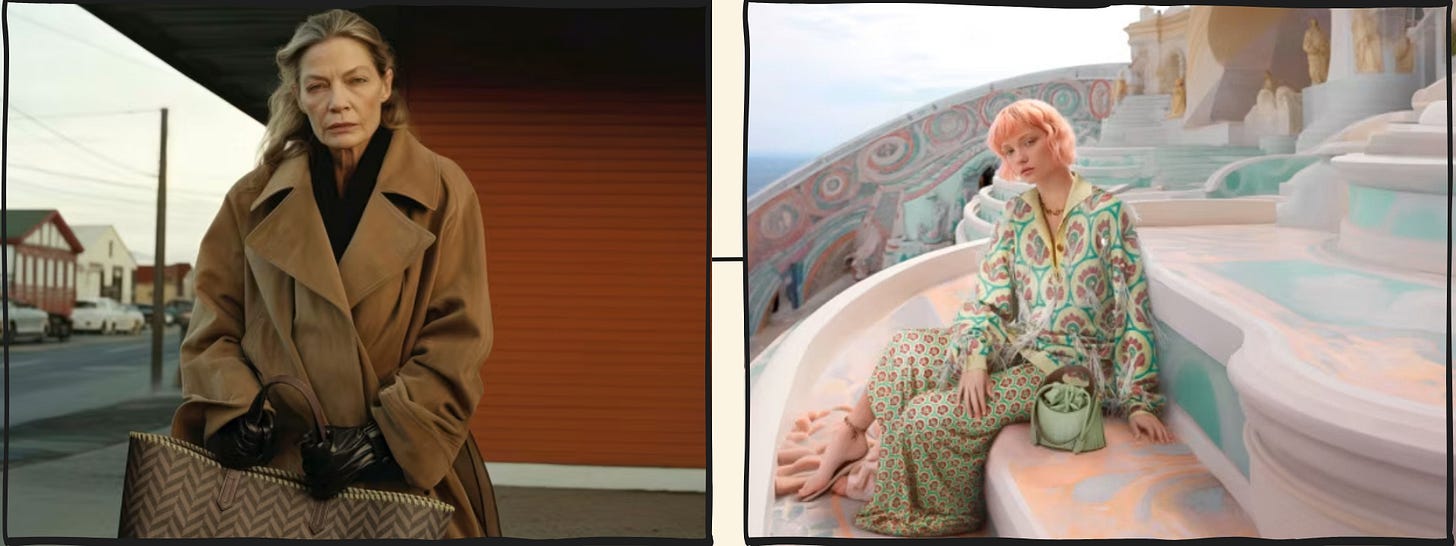

Lets think about that for a moment. No models. No makeup. No stylists. No lighting. No photographers, or maybe some pick-up work. No vanity vans. No location fees. No business class flights. No shipping clothes & accessories halfway around the world for a shoot. Very few brands & marketing teams will be able to resist that. This is the same with Mango’s efforts and others like Etro & Misela, though of course, many do have significant human elements involved.

Models or mascots?

In some ways, AI models can (or should?) be likened more to mascots, than to models or influencers or creators. Brands have a long history of creating characters that represent the brand, perpetuate its personality, spread its word. In that sense, these characters are only separated by technology, not intent. Right?

Not quite. The difference? Mascots have always been obviously fictional- whether soft toys or animated characters or humans playing a part. With AI-generated humans, that line can blur, and quickly. The authenticity that brands are after could well be undermined if these come across as disingenuous.

Here, AI created ‘influencers’ like the Brazilian Lu of Magulu come off a bit better- clearly not human, yet strong enough to rack up a significant following and reportedly have measurable ROI. An inevitable hat-tip here too to Lil Miquela- started in 2016, surely we can we call her one of the OG non-human influencers? Again- her persona, look, following and storytelling is all based on the common understanding that she is a “21 year old robot living in LA”.

There’s also Imma, based in Japan. A ‘fashion model and producer’, she has a quirky sense of humour, often self-deprecating. (Check out this interview with Steve Aoki where she feels she is not good enough). But, for the most part, she is quite evidently… not human. Earlier this year, she did a series with Coach where, unironically, we are asked to ‘travel through virtual worlds with imma as she discovers the #CourageToBeReal’.

Then there’s Aitana, dubbed Spain's first AI model. This 25-year-old pink-haired ‘woman from Barcelona’, is an avid gamer and fitness enthusiast “whose physical appearance is close to perfection”. Her makers decided to create their own influencer to use as a model for brands. "We did it so that we could make a better living and not be dependent on other people who have egos, who have manias, or who just want to make a lot of money by posing.”

So now, modelling agencies offering AI models are proliferating- with good reason. For the agencies, these entities are easier to deal with than real models. They are still ‘representing’ models- Aitana is earning between €3-10k a month. Most effectively, these agencies are able to offer flexibility, reliability, economy, control and speed.

That’s a lot of tick marks. Businesses are not into humans, they are into efficiencies.

Intent.

I don’t mean to call out Puma here. Laila’s first post and then the odd one here and there do refer to an “AI Brain” or “an AI girlie”. Maybe her journey and narrative will prove to be honest, grounded and emotive. But the wider point of fake humans pervading our feeds remains a valid one, especially as the aesthetic lines dissipate between the real, and the not.

I think the differences here lie with the intent- or appearance of intent- with the likes of Laila K and even Aitana, as opposed to Lil Miquela, imma and Lu, who very much ‘own’ their virtual nature. Imma is a “virtual girl in Japan”, Lu is a virtual 3D influencer who looks like one, as is Lil Miquela; whereas Puma’s Laila is a “Digital creator, sports enthusiast & mindful thinker”, and Aitana is a model for hire, and looks the part.

Maybe this difference comes from the intent to create distinctly digital personas, or maybe simply from a gap in resources. But as the craft and technology evolve, and the ability to be real becomes stronger, the need to establish the intent will be more acute.

Connections.

As for the connections humans could make and effects these ‘parasocial’ relationships could have on them? That is another piece to puzzle out entirely. Dr David DeFranza, a professor of marketing in Dublin, suggests AI influencers could actually have less of a negative effect than real-life influencers. "It’s possible when people engage with a known AI influencer they will engage less in comparison than when it’s known to be human. In that sense we would think of this as an animated character". The key here is ‘known’; people casually feed-scrolling are unlikely to stop and put ‘creators’ under a reality microscope.

Yet at the same time, he says, "maybe the opposite is true. Maybe it perpetuates this ideal (of beauty), or makes it more extreme."

Kim Kardashian makes a million euros for an Instagram photo and she doesn't cure cancer. Nobody earns a million euros for uploading a photo to a social network, it seems absurd to me - Ruben Cruz, creator of Aitana.

To end, worth noting that, very significantly, Mango’s use of AI goes beyond marketing and advertising. AI is also helping the company design collections, farming inspiration for fabrics and more. A bot can now create clothing that ‘conforms to the Mango design aesthetic’.

Generative AI is going to proliferate, we know this. The question really is not about stopping the freight train. The question is how will can ensure we keep it real, for both brand authenticity and viewer/consumer transparency.

Related: Mango and others fashion brands leaning into AI across marketing, creative & design.

Related: A survey conducted by SBS Swiss Business School found that customers are increasingly attracted to virtual influencers and perceive them as more trustworthy, credible, and relevant to their preferences. ^